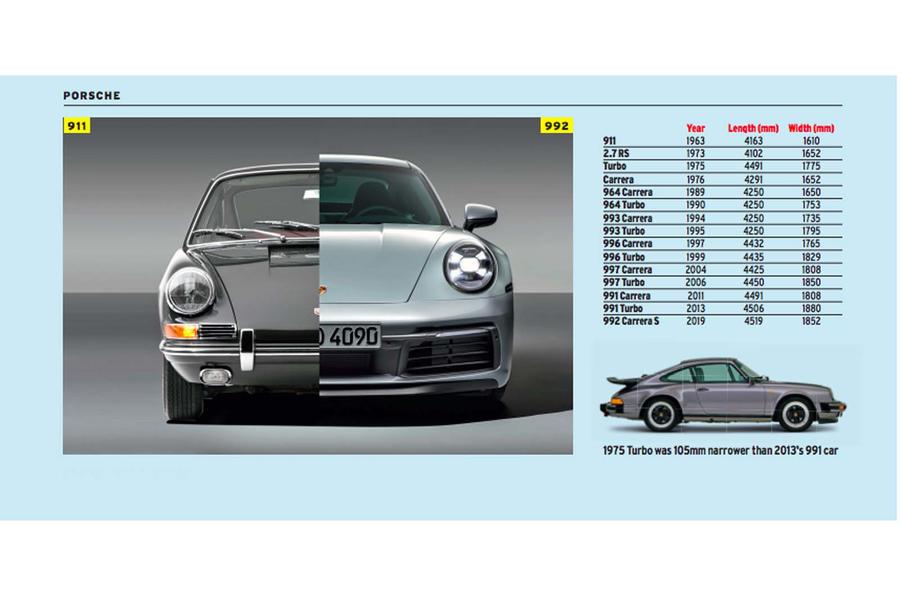

The original Porsche 911 had a narrow 1610mm waistline, the new one has gained 242mm

The increasing girth of cars over the past several decades has been a bone of contention, but the end could be in sight

Do you struggle to squeeze your car down country lanes? Is it awkward to fit in a supermarket parking bay? Is it pointless putting it in your garage, because if you did, you wouldn’t be able to open the door to get out?

Welcome to the expanding world of 21st-century cars. We all know they’re getting bigger and heavier – the Volkswagen Polo is now a bigger car than the original 1974 VW Golf. Most of us know why they are getting bigger, too. To comply with today’s stringent crash regulations – by passing offset, side and roof impact tests, as well as those evaluating pedestrian protection performance – cars require considerable cubic metres of controllably crushable bodywork.

Another reason why cars have become bigger is diet, whether good or bad. People have been getting bigger post-war, both taller through healthier nutrition and sometimes wider, for which we can thank temptation and the wide availability of McDonald’s and the rest. That car makers were taking this into account your reporter learned in 1998, when Ford of Europe’s Richard Parry-Jones, then head of product development, was explaining the reasons for making the 1998 Focus significantly larger than the outgoing Escort. Enlarging humans was one of them. And, of course, if you make a car longer for crashing and taller for its occupants, it will look a little odd if it doesn’t get any wider. But there are some cars – most cars, arguably – that have become needlessly wide.

Roads, on the other hand, are not getting any wider. Recently, a friend witnessed a London traffic jam caused simply by the fact that a Bentley Continental GT and a Range Rover were unable to pass one another in an ordinary street. The resulting jam took 20 minutes to clear. Scenes like this doubtless play out several times a day in some of the capital’s tightest streets.

But as we know, it’s not only luxury cars whose girth is growing. The Golf, now in its seventh generation since 1974 and about to tip into its eighth, is 169mm, or 6.7 inches, wider than it was when Abba were breaking through. Will the next Golf be wider still? Probably. The 1779mm Golf Mk7 is not so far off the 1830mm width of the 1973 Ferrari Berlinetta Boxer, while the current Mini hatchback is a mere inch narrower than a 996-generation Porsche 911 Carrera of 1997. The supposedly diminutive Mazda MX-5 is now slightly wider than the 1973 Porsche 911 RS.

Indeed, the regular fattening of the 911 offers over half-a-century’s worth of road-swamping evidence. The original 1963 edition was 1610mm wide, while the latest 992 is 1852mm broad, some 44mm (1.7in) of that added during the evolution from the 991. The swelling of the 911 is particularly saddening if you like driving: the car is now far less wieldy and agile than most of its predecessors because there’s less on-road margin for error.

Porsche will tell you, as they did at the launch of the 991, that the latest 911 outspeeds its predecessors through slaloms, and demonstrated the fact by wheeling out every generation for timed runs. But this misses the point: the ease of placing the 911 on a real road is further undermined by the ever more rakish angles of its A-pillars, which frequently obscure your apex, in contrast to the pre-1997 models. But reducing visibility is another story. Both this and the growing width of cars is driven as much by design as by the need for crash structures and the increasing size of humans.

Designers fight for the big wheels that give a car the right stance, and if you don’t increase the width of that wheel too, you end up with the tyres of a motorcycle. So big wheels mean bigger wheelhousings, inevitably pushing apart the car’s track if it’s to have a decent turning circle. And then there’s the sheep factor.

The car makers almost always follow each other – it’s harder to justify bucking a trend to your shareholders – and one model enlargement is driven by another. Occasionally there are brave manufacturers who try to break the spiral by maintaining a model’s width (the new Evoque is almost identically dimensioned to the old) or even slightly reducing its size, which both Peugeot and Vauxhall have managed recently. But mostly, cars keep getting bigger.

For many premium and luxury car makers, the US is another reason for the their cars’ door mirrors drifting ever further apart. A Range Rover might look big over here, but on American roads – urban as well as Interstate – it looks small but perfectly formed against the Ford F-150 pick-ups and Cadillac Escalades. The market is too big for these manufacturers to have their products being seen as undersized and overpriced.

There may be hope, though, for all those who struggle to park. Not only is it becoming more obvious that cars are getting too big for towns, villages and cities, but the imperative to reduce CO2 emissions and increase the range of EVs should surely invite some shrinkage. Pushing ever fatter frontal areas through the air costs energy. Something more sylphic simply goes further on a joule of energy. The blame doesn’t entirely lie with car makers either: the mine’s-bigger-than-yours mentality of some buyers swells cars not only outwards but upwards, too.

The irony, from the manufacturers’ point of view, is that they have spent the past 70 years giving us more for less. The market is so competitive that prices barely rise with each fresh model generation, which means that we buyers get more steel, glass, plastic, fabric and rubber per pound we spend with each new model cycle. And adding an inch of width is a lot more expensive than adding an inch of length, the latter merely requiring a slender extra slice of steel, carpet, paint and glass. Add width, and you widen the dashboard, the crash structure, the wheels, the tyres, the suspension arms and more. On sheer material value for money, consumers have been gorging at the car makers’ expense.

How wide are UK roads?

Perhaps surprisingly, there is no absolute definition of how wide roads of various classifications should be in the UK, as explained by the Highways Agency’s Jonathan Turley in reply to a 2011 freedom of information request.

“There are no regulations, as such, for specifying road widths,” he said. “However, there are design documents that provide guidance and advice. The width of a road depends on the volume, type and mix of traffic expected, and other issues. There’s no straightforward answer.” This guidance, he added, is available online.

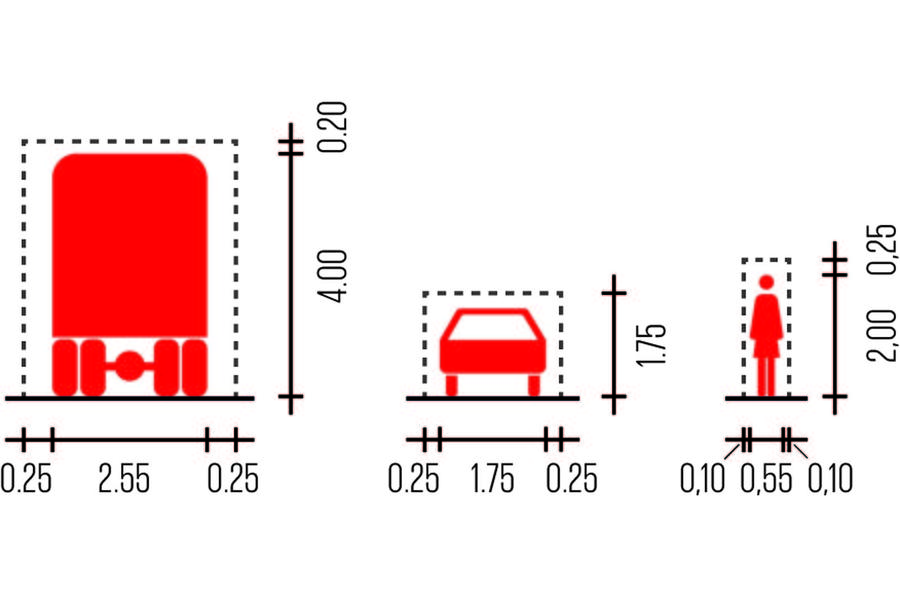

As of 2017, Britain had 246,700 miles of road, minor roads accounting for 83.7% of the total. Motorways make up a mere 2300 miles. There are 29,200 miles of A-roads, 18,800 of B-roads and 196,400 of unclassified roads. That means there are plenty of narrow roads, including some standard residential streets, which can span only 5.5m. Among the Highways Agency’s guidance is a recommended 3.65m width for a single motorway lane, a 3.7m width for a single dual-carriageway lane and 3.65m for other road types. But, in practice, this varies considerably.

Why I chopped a Porsche 911 C4S for an Abarth 124 Spider

Mad, many would say. It’s not as if there was much wrong with the Porsche. It was low-mileage and well maintained yet neither I nor my wife, who was not only the co-owner but initiated the purchase in the first place, was driving it much. It was a classic midlife-crisis car, an impulse buy triggered when she saw a Carrera 4S in a showroom and loved its rear end – which, in the case of the wide-bodied 996 Carrera 4S, is particularly sexy. It wasn’t necessarily the 911 I would buy but, when your wife says she wants to go halves on one, what are you going to say?

But where I live, its ride is a bit harsh, the tyre noise too strident and the bodywork a little too wide to enjoy the immediately available roads to the full in a car with 316bhp and 5.0sec to 62mph potential. The country roads in Hertfordshire are like many others in Britain: sometimes wide enough, sometimes smooth but often quite narrow, potholed and frequently picturesquely lined with hedges and vision-obscuring foliage, not to mention cyclists and horse riders. All of which makes it harder to enjoy this car responsibly.

The noisy, occasionally jarring ride was the main deterrent to using it, and the sense that this was more a long-distance car (at which it’s brilliant, road noise apart) than a dart-about device for local quiet-hours blats. So it went, if not without pangs.

In its place is a new Abarth 124 Spider, a car so much enjoyed on an Abarth event in Sardinia that I occasionally trawled ads – until an unexpected and amazing deal appeared last December on a 23-mile pre-registered car, doubtless fuelled by the need to hit year-end targets. A 33% discount (!) induced a happy succumbing to temptation which has barely diminished with the recent news that, like the Fiat 124 Spider, the Abarth 124 has now been deleted from the UK too.

This car takes 1.8sec longer to hit 62mph, can get nowhere near the C4S’s 174mph top speed and, being an Abarth based on a Fiat based on a Mazda (the MX-5), it’s a bit of a mongrel. But it’s rear-wheel drive, can slip into controllable drifts at legal speeds, makes interesting noises from its Abarth Record exhaust and generally produces tactile joy at speeds much lower than the Porsche. And it’s narrower. Not by much, it’s true – the Abarth’s 1740mm girth 89mm more slender than the Porsche’s 1829mm. But it’s 49mm narrower than the current Golf, 11mm narrower than the Polo and 112mm narrower than the latest, over-size 992 911. This is downsizing with a smile.

Read more

History of the Volkswagen Golf – picture special

Are bigger wheels really ruining ride quality?

Chevrolet C7 Corvette vs Britain’s narrow country roads

Source: Autocar