Despite difficulties, experts are reluctant to completely write off the UK motor industry

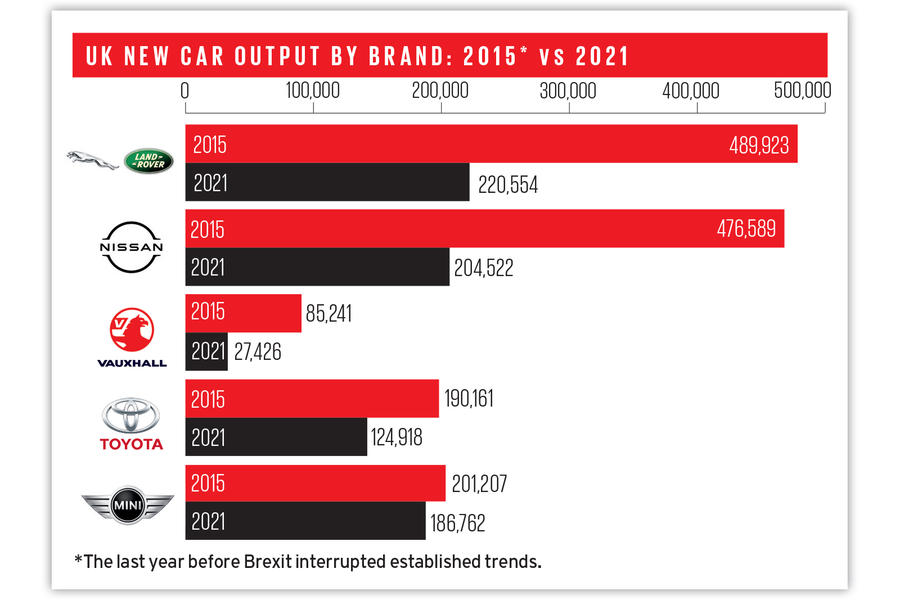

Brexit, Covid-19 and other factors have conspired to halve UK car production levels compared with 2015 estimates

Back in 2015, a few weeks before the Volkswagen Dieselgate scandal and seven months before Britain’s momentous decision to leave the EU, the UK’s motor industry society, the SMMT, voiced an exceptionally bold claim about the future growth of car manufacturing. This history-changing forecast was rapturously received a few weeks later by a confident, 1200-strong audience of industry luminaries at the society’s lavish annual dinner in London’s Park Lane.

The nub of the prediction was that by the end of 2015, British car production would have scored its sixth straight increase – another 15% this time – to top 1.7 million cars. At this unprecedented expansion rate, which back then experts were confident would continue, UK car production would set a new record of two million cars a year for 2016. All seemed right with the car makers’ world.

It didn’t work out that way. The successive effects of Dieselgate, Brexit, Covid, supply chain problems, the uncertainties of electrification, the Ukraine war, energy shortages and the recent waning of Western economies have arrived one after another to send British car production into a tailspin.

Last year’s production (859,575 units) is only half that bullish 2015 figure – and it is also an eye-watering 14% below the previous disaster level set in 2009, at the time of the Lehman Brothers collapse.

Across the UK, this parade of difficulties has caused corporate departures and scalings-down in vital areas.

The big loss has been Honda’s Swindon car plant, and there have been grumblings from Nissan and Toyota, too. The dreaded ‘hollowing out’ of Britain’s much-needed component supply industry has threatened to start again – or did until Covid-created strictures on the other side of the world encouraged companies to think less about globalisation and more about making where they sell.

Still, although experts insist that there are no quick fixes, none is writing off the UK motor industry. It is being sustained by strong and continuing demand for prestige and specialist cars that have always been the UK’s forte – Bentley, Rolls-Royce, Aston Martin and their ilk – and demand continues to be healthy.

Another bright light has been the UK public’s quicker than expected acceptance of battery-electric cars (last year’s sales of 190,000 units exceeded those for the previous five years combined), although even this has been held back by supply problems.

SMMT president Alison Jones, who until recently was group vice-president in charge of Stellantis’s entire UK marque portfolio and has since moved to an even bigger global job, acknowledges difficulties but points to the bright sides.

“If you look at the technology and skills needed to make great cars,” she said, “the UK is in good shape, though of course we always need more people. One of the things we do really well is to embrace new technologies. But we have jobs that need filling in very diverse fields. We must get much better at attracting talent, and it’s urgent.”

However, Jones sees two particular UK difficulties, especially for mass manufacturers: energy prices and the diminished car market. She said: “To sell cars at attractive prices, you’ve got to control costs and build efficiently. A manufacturer looks first for places where manufacturing can be cost competitive. The UK is challenged on that, because of energy costs and market size. We do have a pent-up demand for cars that will improve things, though I wouldn’t like to predict when that will be.”

As we approach electrification, Jones joins many industry leaders in calling for urgent, government-led improvements to the UK’s EV charging infrastructure. The latest predictions say the country’s existing 30,000 public charge points will soon need to be supplemented by 270,000 more.

“We in the industry have already shown we can make great electric cars,” said Jones. “But our customers must be able to charge them.”

Other experts believe the rising need for electrification technology provides a good opportunity for the UK – if the government can act decisively enough.

Andy Palmer, former Nissan COO and Aston Martin CEO, and now a leading light at the Europe-based Inobat gigafactory group, believes the UK’s industry has already had two big expansion chances – its world-leading car export boom after World War II and the arrival of big Japanese manufacturing companies in the 1980s and 1990s – but neither was developed to its true potential. Why? His answer is blunt: “Because governments never acknowledged the importance of engineering and manufacturing and didn’t support them as they should have done.”

Palmer reckons the UK has “one more shot”, geared to the rise of battery-electric vehicles. “We’ve got to start building gigafactories fast,” he said, “and I’m not just talking about a couple. We need at least six of them – and there’s no time to lose. The cut-off isn’t 2030. It’s more like 2027. That’s when consumers will decide buying ICE cars is out of favour. At present, the trajectory of our car manufacturing is in the wrong direction: six or seven of every 10 cars we make are ICE-powered. For EVs, it’s three or four. We’ve got to change.”

Palmer reckons the solution is for the government to “over-index” on helping EV-specific business get established. It’s what other countries do, and we have to compete.

“When the Teslas and LGs come calling, you must do everything you can to accommodate them,” said Palmer. “Sure, we have great R&D here – and once an established business plugs into this, the access to technology becomes ‘sticky’. It’s a great asset. But we must land these big players first. In the UK, we apply rules far too strictly. We may have the advantage of the English language, but it doesn’t pay the bills…”

When things go wrong in the industry, those looking for positives are inclined to cite the UK’s vaunted grasp of pure R&D, especially the close relationship between our most research-heavy universities and the embryo businesses often hived off to develop their raw discoveries. Is this real, or a UK industrial policy fig leaf?

Professor David Greenwood, leading expert in battery research at the high-achieving, university-associated Warwick Manufacturing Group, believes it’s true “in pockets” and cites his own field as a prime example. “When we move from pure innovation into a more commercial R&D cycle, and on to production, I believe we’re currently doing it better than other leading players – Germany, the US and Japan,” he said. “It wasn’t always the case and we’re not perfect. But people like us can help big companies move quickly. We’ve been working with Britishvolt on cell chemistries, and I’d estimate we’ve saved them a year.”

Greenwood says speed is vital, given that the market’s acceptance of electric cars has been faster than expected. “The challenge is to find people to expand the industry,” he said. “We’ll need 70,000 people before the end of the decade and we’ve currently got one-tenth of that number.

“Luckily, here in the Midlands, we have a ready supply of car workers who can be reskilled and it’s just as well. By 2028, most customers won’t want pure petrol or diesel cars. Fossil fuel sales will be down so costs will go up. The industry’s going to change even faster than it has to.”

![]()

Like most experts, Greenwood believes the UK’s specialism will continue to be in higher-end cars, where ‘Britishness’ continues to count. And we’ll keep excelling in racing tech because of our excellence at small-company R&D. But Greenwood isn’t so bullish about any expansion in our ability to make cars for the mass market. “Manufacturers look at the economics of geography,” he said, “and there’s no doubt the UK isn’t the best there. Brexit hasn’t helped. If you’re a big supplier or manufacturer in Europe, you look at the transactional cost of selling in the UK and you choose customers closer to home.”

Birmingham University’s Professor David Bailey, a much-quoted expert on industrial production and business economics, believes the UK car industry will take years to recover from the decline that started after 2016. Those reverses created what Bailey labels “an inadvertent reduction of investment”. The industry had recently started to hope for an easing of the downwards pressures, he says, but we’re now entering “a phase of demand-size constraints geared to one of the biggest squeezes on living standards for a very long time”.

If there’s room for optimism, says Bailey, it needs to be guarded. It will be at least 2025, he estimates, before production exceeds a million cars again, and our muchpublicised need for six to eight battery gigafactories to propel the change to electrified cars is lagging badly compared with the “massive investment” across the EU, reputed to have 35 plants in build or in prospect.

The hope for UK car manufacturing, believes Bailey, is what he calls “the phoenix industry”, a strong and numerous body of small and fast-acting suppliers who operate at the cutting edge of technology and do things extremely quickly. Bailey labels this group “a fundamental success” and believes they can deliver the UK a unique future advantage.

“I don’t want to be too pessimistic,” he said. “We have a big car market here. And we have our phoenix industry. With some luck, I could see car production hitting 1.7 million units again – not the peak expected before Brexit and Covid but still strong. But it would take the right kind of government help, and that would mean returning to days when people like Peter Mandelson, Vince Cable and Greg Clark truly understood the industry. Just now, however, our politicians seem a bit preoccupied.”

What does it mean for buyers?

The dearth of UK car production continues to make life difficult for consumers in this country – and it will do so for some time. The supply of semiconductors remains the primary shortage. (Supply to makers of the most expensive cars, such as Rolls-Royce and Bentley, is significantly better than to those who make more mainstream cars.) However, other components and even primary raw materials, such as steel, continue to be hard to source.

Speaking at the recent Paris motor show, Stellantis boss Carlos Tavares said there were signs of the difficulties easing, although unevenly, and he expects the computer chip problems, at least, to be “over” by the beginning of 2024.

This shortage of new cars has created an extraordinary overheating of the UK’s market for nearly new cars, although the latest dealer reports say prices have eased a little from mid-year sky-high levels because prime stock is hard to find, just as economic difficulties and the onset of winter combine to discourage less committed buyers.

However, with experts predicting that UK new car production will remain below one million units a year until 2025, it is likely that buyers will still have to compete hard for the best used cars through 2023, at the very least.

Source: Autocar