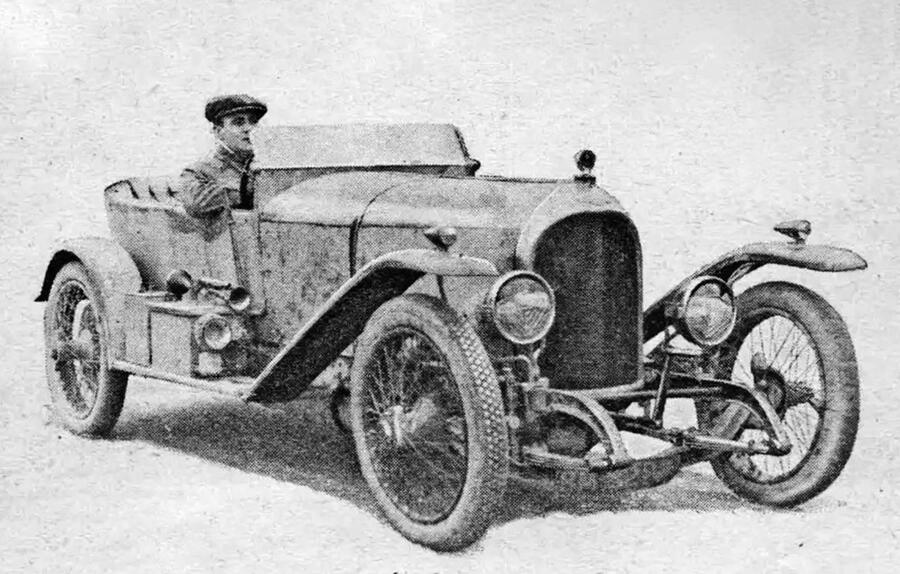

Production of 3-Litre chassis began at new Cricklewood works in 1921

WO Bentley started out designing engines for fighter for planes and racing cars for French brand DFP

It has become an all too familiar tale in this era of new technology: a new company emerges from nowhere, boasts of an amazing car and promises that production will begin very soon – and then goes suspiciously quiet.

History is repeating itself, as one 105-year-old Autocar article shows: “Since the announcement in May 1919 that a Bentley car was to be produced, over two years have rolled by. Motorists to whom the chassis appealed especially have been wondering what was happening, why no cars succeeded the original experimental chassis, and, little by little, the rumour grew that the Bentley never would be a production job.

“Within a few weeks, the first car is to leave the works in the hands of its owner, and there will follow a steady output of five cars a week. These facts alone are the firm’s answer to its critics, but one may be forgiven for dwelling a little on the difficulties which have had to be overcome.

“First, there existed no works, no staff and no experience of manufacture when the car was drawn out. Then the chassis had to be tested to the utmost limit.”

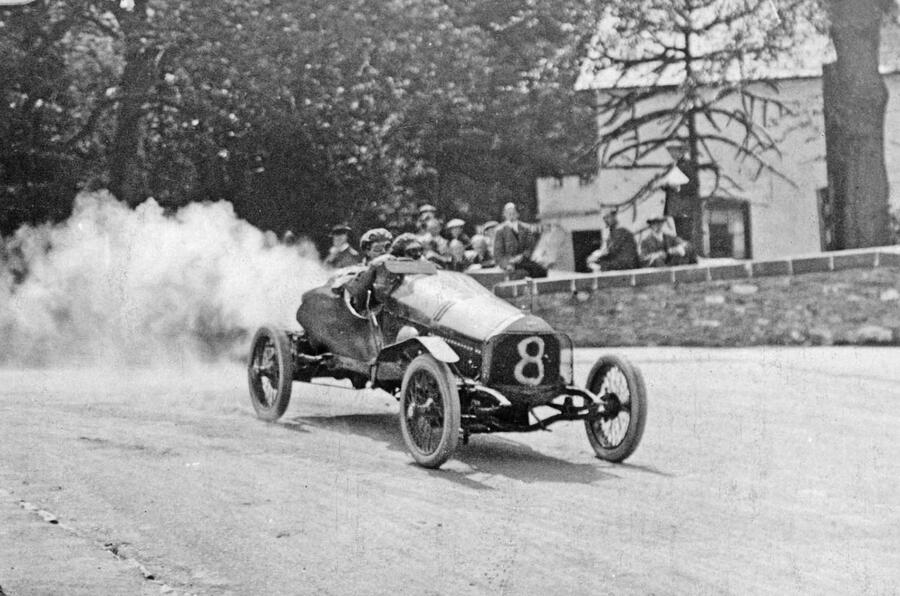

Amazingly, Bentley had let Autocar’s Sammy Davis drive the experimental prototype – with its lashed-up, mud-filled, open body – in January 1920. He reported: “The general behaviour of the chassis suggested an entire absence of effort combined with more than ordinary tractability.

Enjoy full access to the complete Autocar archive at the magazineshop.com

“All this was done with the air of a lithe, active and speedy animal straining a little on the leash. Presently a long stretch of familiar road, quite deserted, unrolled ahead. Instantly the exhaust changed its note from a purr to a most menacing roar, the white ribbon of road streamed towards the car, while the backs of the seats pressed hard upon one’s shoulder blades.

“Every part of one’s being urges greater speed in the fierce, wild intoxication of a moment supreme above all others in the life sensations of man.”

Company founder Walter Owen Bentley would later recall: “How I wished we had had the cars we could have sold a dozen times over as a result of that piece of publicity!”

Indeed, even when a 3-Litre was displayed at London’s motor show that November, its engine remained incomplete under a locked bonnet.

Not that Walter was some naive amateur – far from it. Educated as a railway engineer, he had joined the automotive industry aged 24 back in 1912, he and his brother Horace Millner Bentley becoming the sole UK dealers for French firm DFP. He had started tinkering straight away, upgrading the cars’ engines in order to break speed records and win races, earning high praise from Autocar.

Chief among the modifications was weight-saving aluminium for the pistons – his inspiration being a paperweight that he saw in DFP’s Paris factory. Of course, war then broke out, and Walter suggested to officials that his techniques be put to military use – leading to him designing the rotary engines used in Sopwith’s famous fighter planes.

You might assume royalties from this funded the post-war foundation of Bentley Motors, but Walter was rewarded a “pittance” of £8000 for it, and that only after a “beastly and tiresome” court case. Helping rather more was a boom in car sales: Horace’s team brought in some £20k from DFP sales in 1920 alone.

But there was another side to this: car factories and suppliers had no need for new clients, meaning that, in Walter’s words, “to design and build a new car in 1919 without substantial capital was like being cast on a desert island with a penknife and orders to build a house”.

Somehow the brothers managed to secure a site for a new factory (well, “a small brick building”) in countryside just north of London.

Walter assembled a “small but exceptionally good” team at Cricklewood, working through 1921 until the day when a chassis was ready for Bentley’s first customer.

He was one Noel van Raalte, chosen specially because he “was very rich, was very sociable and had excellent mechanical knowledge” and would thus be “an excellent testing and propaganda tool”.

A correct assumption, proves his October 1921 letter to Autocar: “The reason I bought a Bentley was because of its exceptional performance in all respects and the care and attention which I believed had been given to its production. I can [now] truthfully say that I am more than pleased that I waited the considerable time I did while the car was being put into production.”

Source: Autocar